Shining a Light on Labor Market Data that have Leading Economic Indicator Properties

Former JPMorgan Chase Global Chief Economist & PH.D. in Economics

We often hear that the Federal Reserve should never use labor market data to set the federal funds rate each month because the data represent lagging economic indicators. The problem with this argument is that it is simply untrue! A subset of labor market data in the monthly JOLTS Survey generated by the BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics) has proven to be reliable leading economic indicators that the Fed has used in its monetary policy deliberations.

Like the Rolling Stones that have been an integral part of our culture, highlighted in the "Shine a Light,” 2008 documentary, the monthly employment report is an iconic report released each month. In this newsletter, we wish to broaden the use of labor market data as leading and lagging economic indicators like the broad appeal that the Rolling Stones have enjoyed across demographic groups! Our hope is that the reader will get greater "Satisfaction" from analyzing labor market data after reading this report!

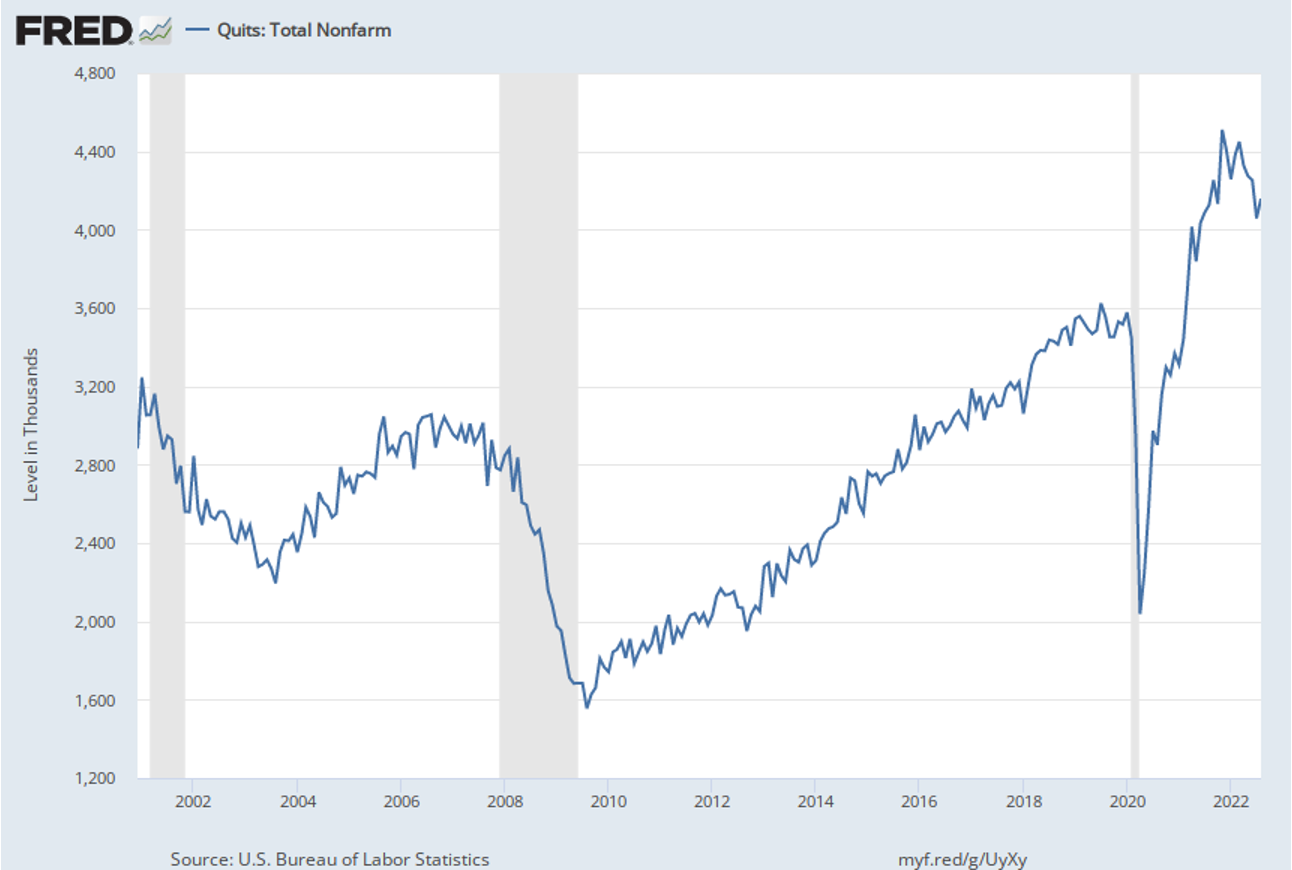

We know the Fed pays close attention to the JOLTS Survey by the numerous times that Fed Chair Powell has referenced the ratio of Job Openings to Unemployed individuals as a guide in its battle against inflation. Former Fed Chair Yellen also openly cited the number of “Quits” back in 2013 as one of her favorite labor market indicators!

Such features were highlighted in a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) paper discussing the monthly "Job Openings" and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). Interestingly, this research revealed that these variables in this survey act as leading economic indicators and provide an opportunity for investors and policymakers.

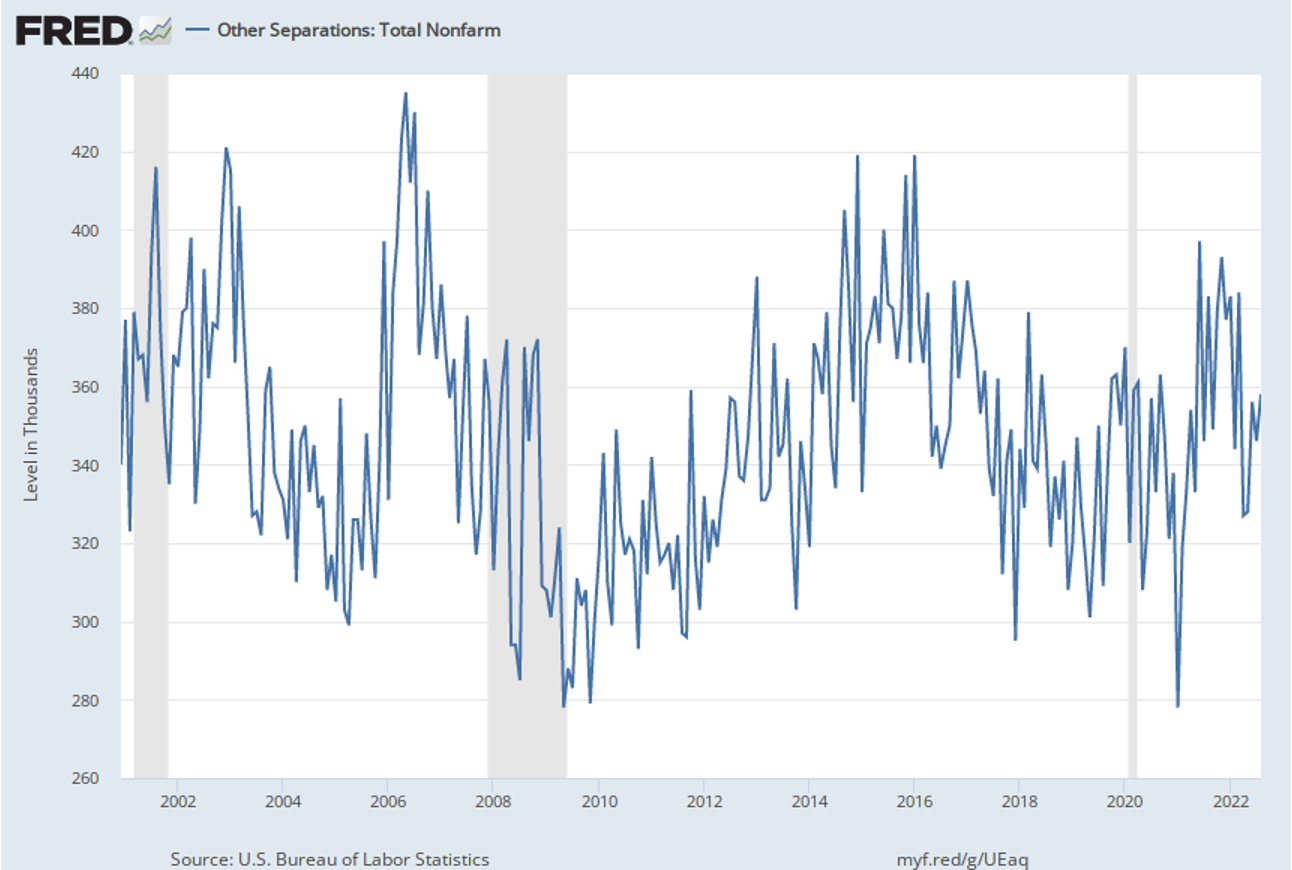

Total separations occur when an employee quits their job, gets laid off, retires, is transferred to another division within the company, or suddenly leaves the company due to disability or death. Other job separation components occur due direct employee actions (e.g., Quitting), or an employer action (e.g., laying off an employee). This category captures actions initiated by workers and employers. Finally, the departure of workers due to death or disability is often not directly controlled by an employee.

The “other separations category” provides an exciting combination of employer- and employee-motivated actions. Retirements usually rise during favorable economic periods and tend to be postponed during recessions due to increased economic uncertainty.

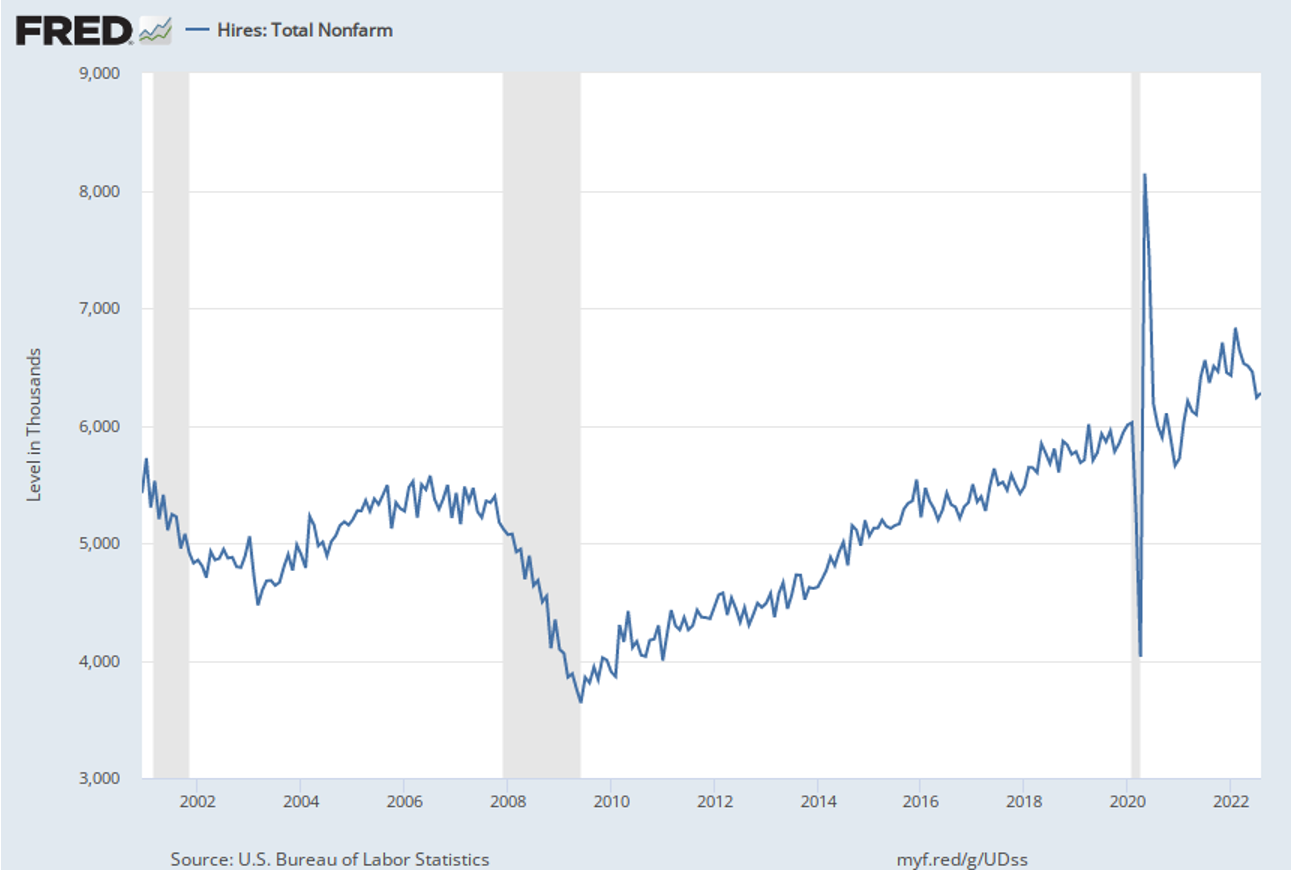

Using data before the Dec. 2007 – June 2009 recession, we find that the number of New Hires peaked in Sept. 2005, the number of Other Separations peaked in May 2006, the number of Quits peaked in Aug. 2006, and the number of Job Openings peaked in April 2007. All these JOLTs Survey components served as leading economic indicators compared to the monthly employment numbers from the Household and Establishment Surveys that served as lagging economic indicators by continuing to rise until the recession began.

The star performer of the JOLTs Survey is the number of “Job Hires.” This leading economic indicator peaked in Sept. 2005, i.e., 27 months before the Dec. 2007 recession. This variable peaked in May 2020 and projected the start of a U.S. recession in August 2022. Some might believe this peak (just one month after the last recession ended) as a dead cat bounce from the +2.0 million monthly drop in Apr. 2020 when the economy was in a deep recession (Feb. 2020 – Apr. 2020). Adjusting for this anomaly, the latest peak in this series occurred in Feb. 2022 and suggests the next recession will begin in May 2024.

Our second best-performing leading economic was the Other Separations data series. That series peaked 19 months before the start of the Dec. 2007 recession. It then dropped sharply during the recession and recovered as the economy entered the economic expansion.

This variable is affected by actions initiated by employers and employees and may provide a better picture of labor market conditions. Recently this component hovered above the reading observed during the last month of the recession in all but two months of that long-lasting economic expansion. It peaked in June 2021 and predicts the next recession will start in Jan. 2023.

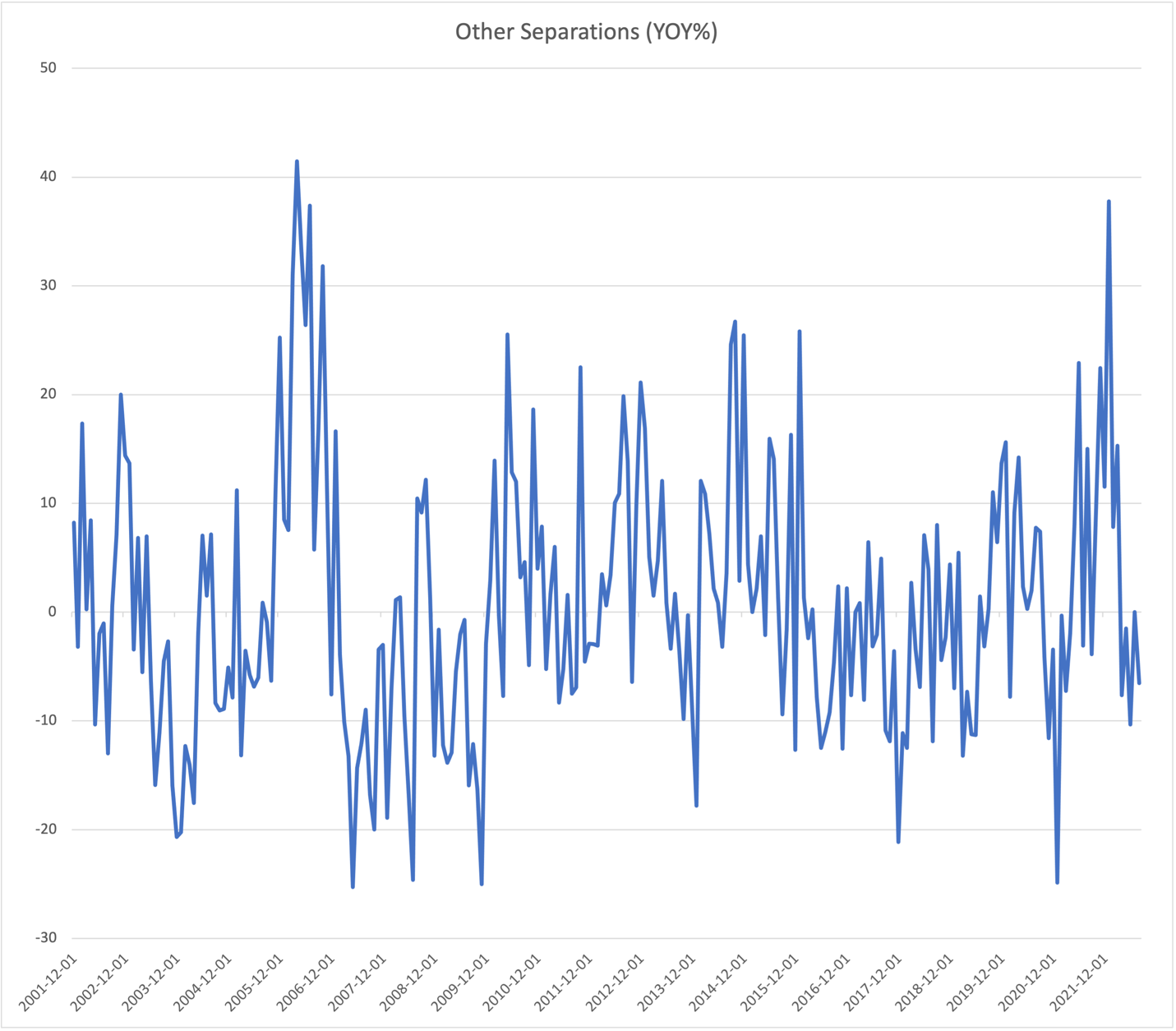

One good way to see the deceleration in this data series number is to look at the year-over-year percentage changes in this series dating back to its +37.8% peak in Jan. 2022. These figures suggest that the U.S. economy is slowing and at heightened risk of entering a recession.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, JOLTS Survey

Former Fed Chair, Janet Yellen’s favorite indicator from the JOLTs Survey is the number of “Quits.” The variable peaked in Aug 2006, or 16 months before the start of the Dec 2007 recession. Given that this variable peaked in Nov. 2021, the next U.S. recession should have begun in March 2022!

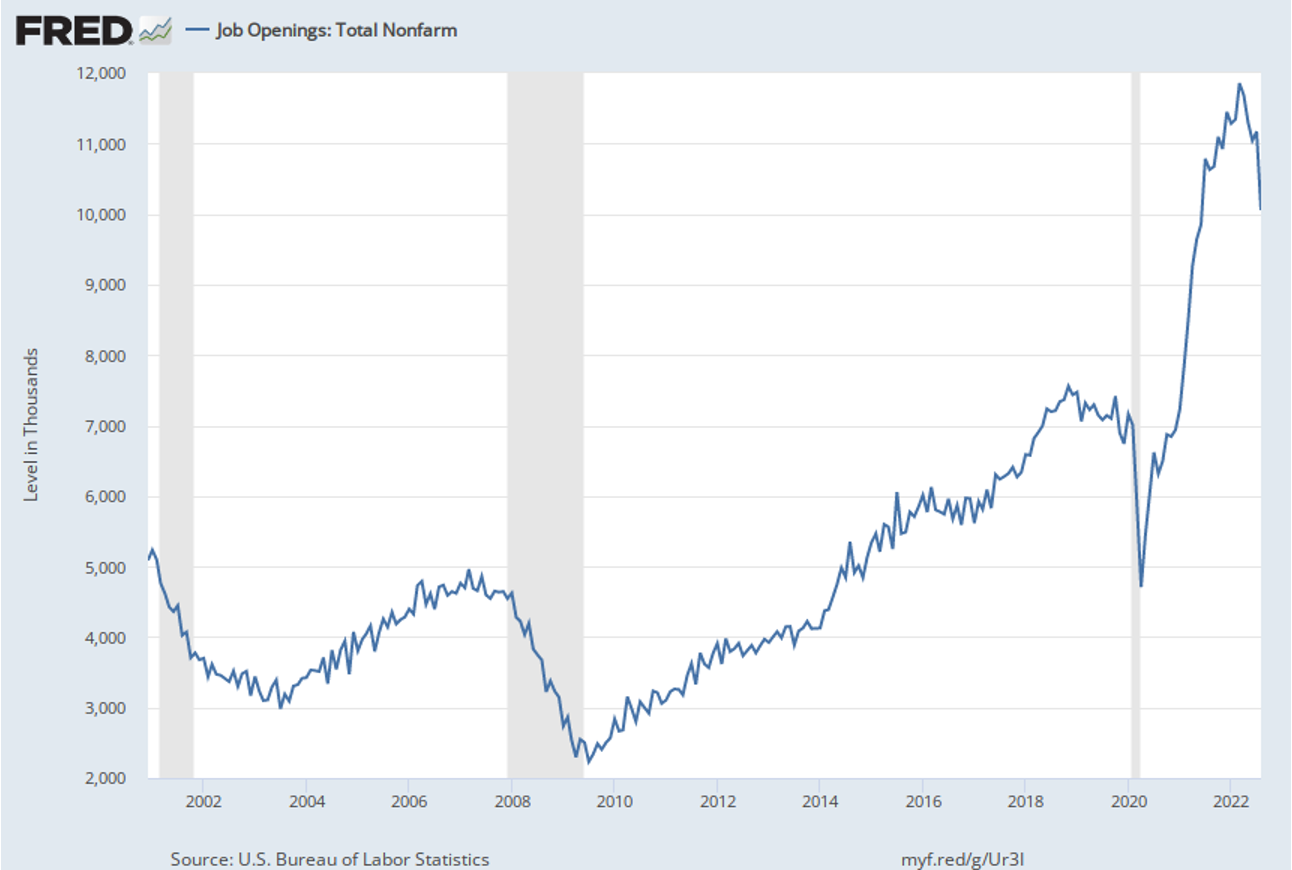

The number of Job Openings that Chair Powell has cited as being too high and likely causing higher wages peaked eight months before the Dec. 2007- June 2009 recession. Given the March 2022 peak in this series, the next recession should start in Nov. 2002.

Summary and Conclusions:

Using a weighted average of these four leading indicator components based on how accurate they were in forecasting the 2007-2009 recession, the next one should begin in Jan. 2023. We assigned a 40% weight to the indicator that called for the recession with the longest lead time, a weight of 30% to the second-best, 20% to the third-best, and 10% to the fourth-best leading indicator.

Our results reveal that some labor market data are valuable leading economic indicators and some justification for the numerous times that Chair Powell and former Fed Chair Yellen have cited the JOLTS Survey to explain monetary policy decisions. The only regretful aspect of this valuable data is that the number of observations is limited as its data goes back to Dec. 2000.

Given our results, one can understand why Fed Vice Chair Brainard and Chicago Fed President recently highlighted the risk of raising interest rates too quickly as the odds of recession rise.