The Ghost of Stagflation: Is it Creeping Back In?

Former JPMorgan Chase Global Chief Economist & Current Global Keynote Public Speaker

This once-dismissed economic specter—defined by the rare and toxic combination of high inflation and negative or stagnant economic growth—is back in the headlines. But before anyone can issue a full-blown economic disaster alert, one must examine what true stagflation looked like in the past, how today’s conditions compare, and whether the U.S. is on the same trajectory.

In the past 50 years, stagflation has been observed only a few times. Those specific instances exhibit a recognizable pattern: soaring inflation, declining real GDP, and increasing unemployment. Here are four notable historical examples:

1970: The U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 5.6%, and the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) price deflator rose by 4.7%. Yet U.S. real GDP shrank by -0.3%.

1974: Triggered by the OPEC oil embargo, the CPI soared by 11.1%, and the PCE by 9.1%, while real GDP decreased by 0.6%.

1975: Stagflation persisted, with the CPI rising by 9.1%, PCE at 7.0%, and a further decline of 0.2% in GDP.

1980: The second oil crisis pushed inflation even higher—CPI surged to 13.5%, PCE to 10.3%, while GDP contracted again by -0.3%.

It wasn’t until Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker enacted one of the most aggressive monetary tightening in U.S. history—raising interest rates to 21% by 1981—that inflation was finally brought under control. The cost was steep: a deep recession, widespread unemployment, and a decade of structural economic adjustment. However, by 1983, inflation had cooled to 3.2%, setting the stage for the long economic expansion of the late 1980s and 1990s.

These were not merely inflationary periods; they were times when the economy faltered and prices surged, leading to policy paralysis and widespread economic distress. Unemployment peaked at 8.5% in 1975, and conventional financial tools proved inadequate for addressing the challenge. Economic stimulus seemed to worsen inflation, while monetary tightening threatened to deepen the economic downturn, leaving policymakers with fewer options to choose from.

This period also necessitated a reevaluation of the Phillips Curve, which suggested an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. The stagflation of the '70s and early '80s posed a significant threat to that model. Since that time, the U.S. has flirted with inflationary pressures—most recently in the post-pandemic recovery years—but never again suffered through stagflation as it was defined in the Volcker era.

Where Are We Today?

First, credit should go to the Trump administration for the deceleration in inflation, as the latest April 2025 data reveals that the CPI is moving lower and getting closer to the Federal Reserve’s 2.0% growth target, albeit it remains above the Fed’s 2.0% target. However, when the President claims that there is virtually “no inflation,” such words should be taken with caution because headline and core consumer prices continue to rise at a pace above the Fed’s inflation growth target. Anecdotally, it is also hard to believe that inflation is non-existent when a bucket of popcorn at the snack window in the Super Nintendo World at Epic Universe theme park in Orlando, Florida, sells for $40.00!

However, in the interest of nonpartisanship, we must also note that when the Federal Reserve first labeled the rise in inflation as “transitory” during the Biden administration in May 2021, the CPI was increasing at an annual growth rate of 5.0% and later peaked at 9.1% in June 2022, ultimately proving this early assessment wrong!

It is encouraging that, unlike the rhetoric circulating a few years ago, few are insisting that prices need to return to pre-COVID levels before we can declare victory over inflation. That standard is higher than any ever used in history and was invoked mostly for partisan reasons. This means that as inflation rates move closer to the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target, policymakers should be prepared to loosen monetary policy and cautiously declare a ceasefire on the war against inflation.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Nonetheless, the economic backdrop in 2025 remains complex. Growth has slowed, and inflation has proven sticky. But is this stagflation? No, not yet. However, the S&P Global preliminary purchasing manager survey for May 2025 recorded their highest monthly inflation readings since September 2022! The University of Michigan Sentiment Survey also reported that consumers expect U.S. consumer prices to rise by +7.3% (in the preliminary May 2025 report), over the next 12 months!

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

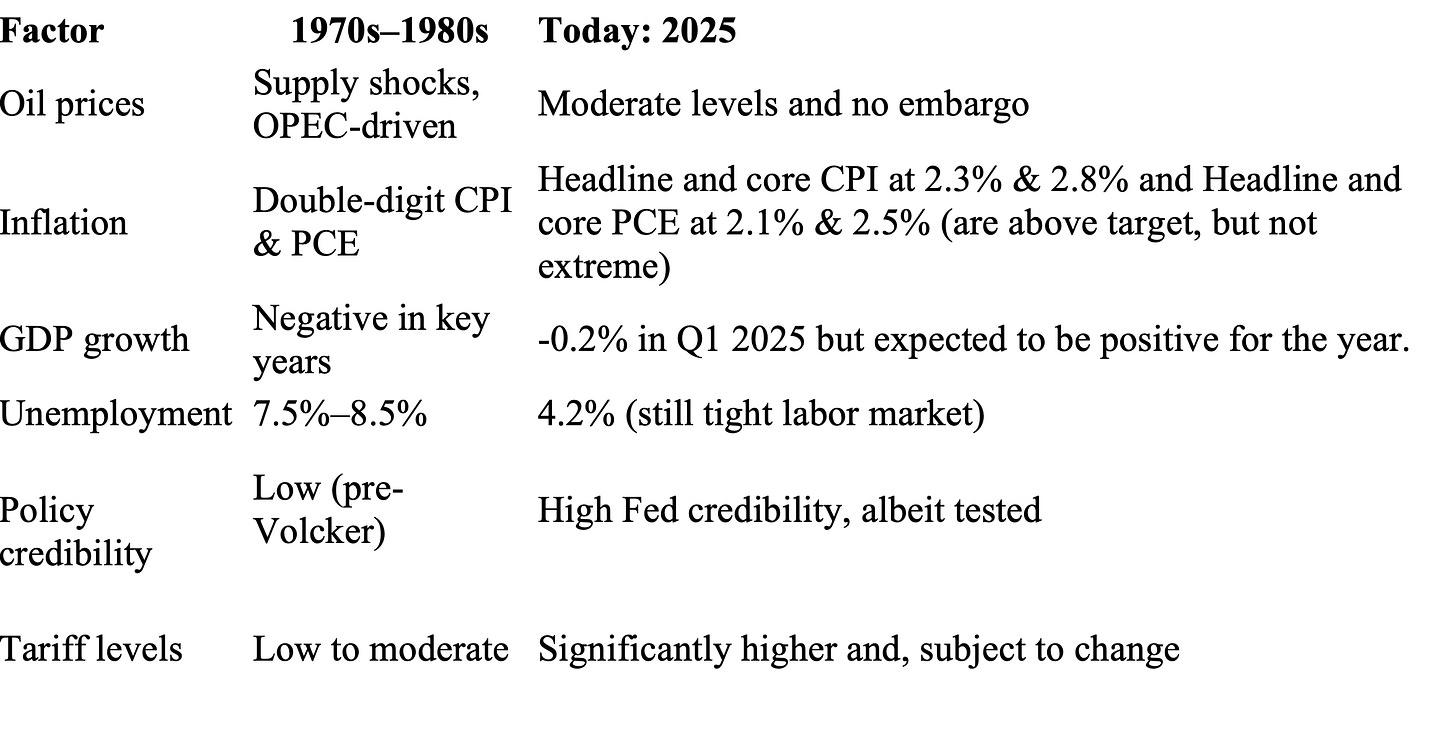

While it’s true that we are not experiencing inflation in double digits as we did in the 1970s, both the CPI and PCE inflation metrics are above the Fed’s 2.0% target. According to April 2025 data, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) is rising at a yearly rate of 2.3%, while its core reading is increasing by 2.8%. In contrast, the PCE (released on May 30, 2025) is growing at an annual pace of 2.1%, while its core reading is rising by 2.5%.

At the same time, U.S. real GDP growth may slow to the 1–1.5% range for the 2024 calendar year from a 2.8% growth rate in the prior year. The unemployment rate remains at 4.2%, but cracks are emerging in the labor market, particularly among part-time and temporary workers. While these conditions are not reminiscent of stagflation in a historical sense, they do pose a risk.

Can Tariffs Ignite Stagflation?

One major driver of inflation risk today is trade policy, which remains shrouded in uncertainty following the International Court of Trade’s unanimous ruling that actions taken under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) were illegal. This ruling was followed by a second federal judge, who ruled that other tariffs imposed on China and other countries were also deemed unlawful. Nonetheless, these rulings were upended by a Federal Appeals court decision to allow the tariffs to remain in place until both sides have had sufficient time to work through the appeals process.

With the consensus view that higher courts (e.g., SCOTUS) will side with the President, tariffs are back in vogue, with trade negotiations in full swing alongside threats to impose a 50% tariff rate on all European imports, albeit this threat was also delayed to July 9, 2025. The problem? Tariffs are generally inflationary. Still, in the interest of nonpartisanship, let’s review the competing views on this topic. Some argue that U.S. tariffs result in only a one-time price increase, an argument that Fed Chair Powell has sometimes used. In contrast, others suggest that if U.S. corporations absorb them, they will primarily result in lower corporate profits, shielding consumers from the impact of higher prices.

However, with a projected profit margin of 13.0% for S&P 500 companies in Q4 2025, and even lower profit margins for smaller companies, it may be challenging for companies to absorb tariff rates of 25% or 30%. Other studies indicate that tariffs will be applied more broadly to investment goods and less to consumer goods. If this occurs, consumer prices will rise less sharply; however, the economy could experience a decline in future investment, which may negatively affect productivity and future economic growth, albeit with less detrimental impacts in the short term.

The bottom line is that if U.S. companies fully absorbed a tariff rate that was more than their expected profit margins, the result would not be sustainable. Fortunately, unlike the oil price shocks of the 1970s, tariffs are policy-induced and can be easily reversed.

Key Differences: Then vs. Now

To determine if we’re headed for true stagflation, it’s essential to distinguish today’s dynamics from those of prior stagflation periods:

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

Here are several key indicators to watch:

Real GDP growth: Although Q1 2025 was slightly negative at -0.2%, this was due to special factors, such as a surge in imports resulting from firms' actions to avoid tariffs. Expectations for real GDP growth in Q2 2025 are firmly positive at +2.2% according to the latest forecast by the Atlanta Fed GDP Nowcast forecast model.

Core inflation: If PCE and CPI both remain above the Fed’s inflation target and stay there, the Fed may be forced to delay cutting its policy rate.

Unemployment: A sharp uptick in joblessness, combined with sticky inflation, would be a clear red flag. However, the surge in immigrant deportations may suppress the rise in the unemployment rate even if the economy slows.

Tariff escalation: Further protectionist measures could exacerbate inflation and dampen economic growth.

While the U.S. is not currently facing imminent stagflation, the FOMC hasn’t ruled out the possibility that tariffs could lead to stagflation.

This suggests that tariff and interest rate policy decisions will determine whether we can avoid a repeat of the 1970s and 1980s. In the meantime, our Federal Courts and, ultimately, the Supreme Court, will also have a say in determining the legality of tariffs as the administration navigates around these speed bumps.

To paraphrase a popular economic phrase: "It’s not stagflation until it is.”