The Surprising Disconnect Between Fed Rate Cuts and U.S. Mortgage Rates

Former JPMorgan Chase Global Chief Economist (Ph.D. in Economics) & Current Global Keynote Speaker

Getty Images: Dejan Marjanovic

The relationship between the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate, long-term U.S. mortgage rates, and long-term Treasury yields is complex, shaped by a wide variety of economic, financial, and market sentiment factors. While it’s tempting to think that a significant cut in the federal funds rate—say, by 200 to 300 basis points—would directly lead to similar decreases in mortgage rates or the 10-year Treasury yield, historical data from the 1960s to today shows this rarely occurs. In our nonpartisan review of the data, we also examine why the relationship between the federal funds rate and long-term rates may vary over time.

Does a Fed Rate Cut Lead to Lower Long-Term Yields?

The answer is yes if markets expect the move to occur against a backdrop of weaker expected economic growth or lower future inflation. However, suppose financial markets anticipate that economic growth is likely to accelerate or that inflation could rise due to the short-term impact of 20-50% tariff rates. In that case, mortgage rates or the 10-year Treasury yield are unlikely to decline.

However, the recent economic debate has focused on whether the U.S. can achieve better-than-potential growth or even surpass expectations. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) increased its forecast for real GDP growth after incorporating the effects of “The Big Beautiful Bill Act,” projecting +2.4% over the next decade without recessions, up from its previous estimate of +1.8%. In contrast, U.S. Treasury Secretary Bessent heavily criticized these figures as too conservative, claiming that the actual growth rate will average 3.0%. The only agreement between the U.S. Treasury and the CBO is that the U.S. economy will not experience a recession over the next 10 years. Since U.S. potential growth is estimated at 1.8%, any growth rate above this should be considered highly impressive! In light of the 0.5% decline in U.S. real GDP in Q1 2025, increasing economic growth to an average of 2.4% or 3.0% is unlikely to exert downward pressure on long-term interest rates due to concerns about growth.

What Does History Teach Us?

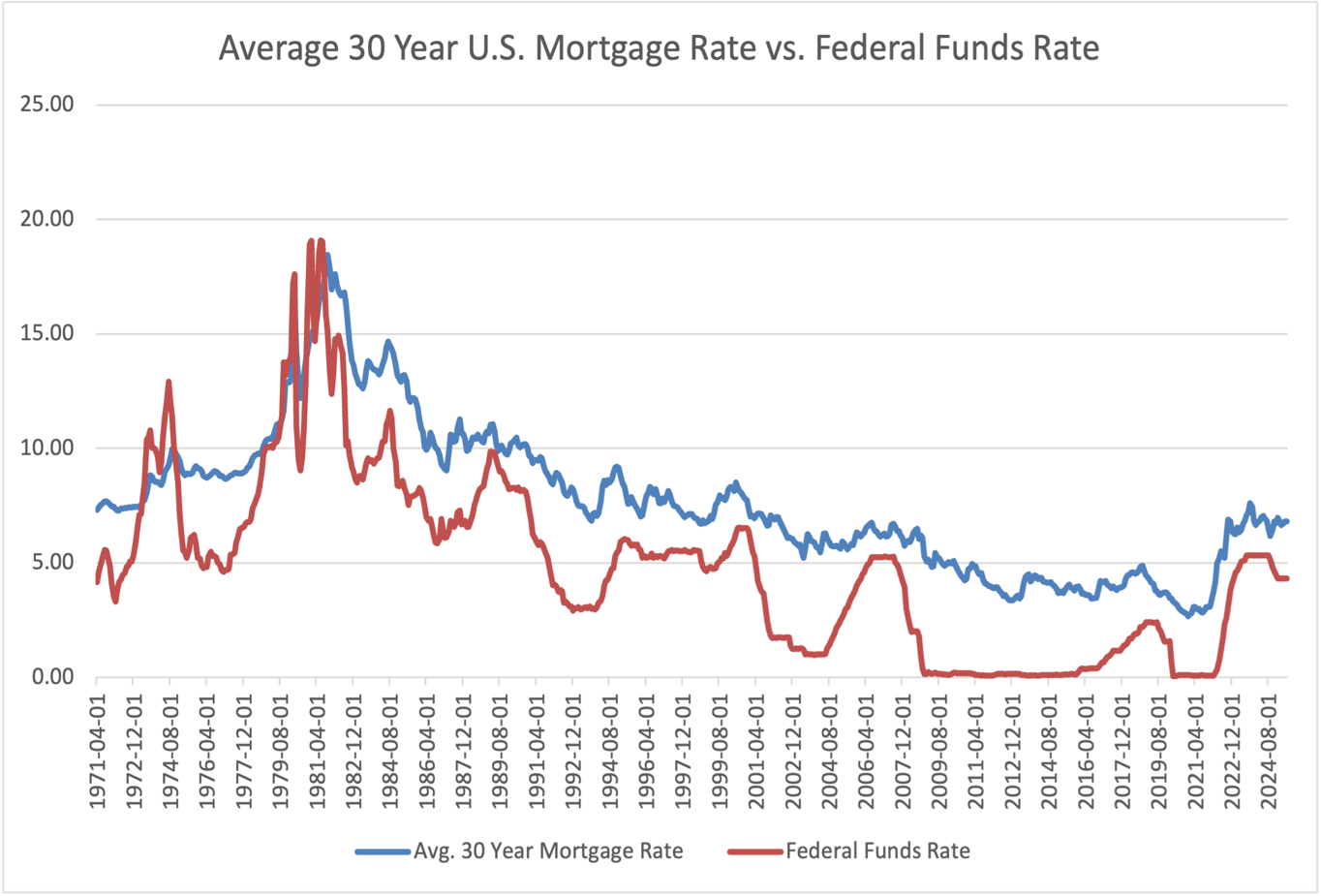

In prior periods (e.g., from 2009 to 2016, the 2020 global pandemic, and in many other instances), reductions in the federal funds rate have often failed to lead to equivalent reductions in U.S. mortgage rates.

The federal funds policy rate and the 10-year Treasury yield or the 30-year mortgage rate move in tandem only when the determinants of long-term rates and the policy rate are entirely aligned with each other. In most instances, history reveals that these different interest rates move loosely in tandem, or not at all, with each other.

Source: Freddie Mac and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Fred Database

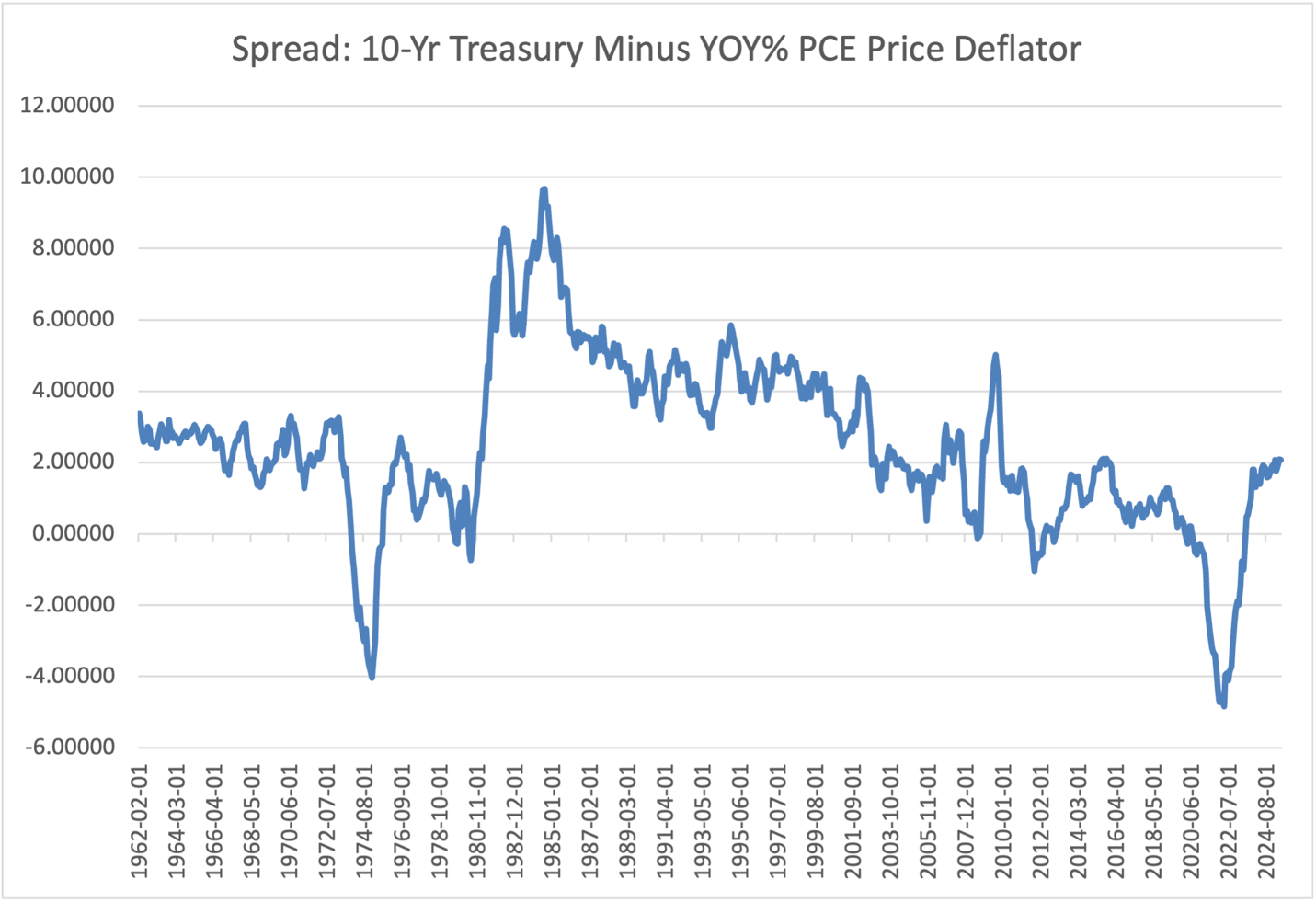

As one can directly observe, the spread between the 10-year Treasury yield and the federal funds rate has fluctuated between +4.0% and -6.0%. With such variability, how can anyone credibly say that lowering the federal funds rate will automatically lead to a lower 10-year Treasury yield, or, for that matter, an equivalent reduction in the average 30-year mortgage rate?

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

This is why it is important to remember that the federal funds rate is a short-term rate influenced by the Federal Reserve, while long-term interest rates like the U.S. 30-year mortgage rate or the 10-year Treasury Yield are often controlled by other factors, like global policy uncertainty, long-term expectations of inflation, and business cycle expectations.

Global Policy Uncertainty

Policy uncertainty affects long-term yields by influencing the rate at which investors, including foreign investors, demand to lend to the U.S. Treasury over extended periods. Currently, the evidence indicates that the level of global uncertainty among the 20 major countries is at an all-time high. Factors driving this uncertainty include geopolitical events, fiscal policy—especially its potential impact on future federal budget deficits—U.S. tariffs, and perceptions of how U.S. economic policies might influence long-term inflation.

Source: Academic research by Scott R. Baker, Nick Bloom, Stephen J. Davis, and the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

U.S. Economic Outlook

Long-term U.S. Treasury yields also tend to decline when investors anticipate slower economic growth or a recession. As of July 12, 2025, Polymarket.com, an international betting platform, estimated the odds of a U.S. recession in 2025 at a very low 19%, down from a peak probability of 66% on April 6, 2025. This is another factor that will put upward pressure on long-term interest rates even if the Federal Reserve were to quickly reduce its policy rate by 200 to 300 basis points as demanded by the White House.

However, for those hoping that a U.S. recession would lower the 10-year Treasury yield or mortgage rates, if such a recession were severe, mortgage rates might still fall less than any decrease in the federal funds rate due to increased credit risk or market instability.

Source: Polymarket.com

Inflation Expectations

Between 1980 and 1990, the U.S. experienced rising and volatile inflation, which began in the late 1960s and continued throughout the 1970s. Despite periodic cuts in the federal funds rate, the 10-year Treasury yield (which significantly impacts U.S. 30-year mortgage rates) often remained high or even increased, as markets doubted the Fed’s commitment to fighting inflation, which explains why credit markets demanded as much as a 10% inflation premium during the mid-1980s.

During this period, the 10-year Treasury yield increased from 4% in the early 1960s to nearly 16% by the late 1970s, closely tracking actual inflation and rising inflation expectations.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

To combat inflation, the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker raised the federal funds rate to historic highs. As inflation was brought under control in the mid-1980s, long-term yields and mortgage rates gradually fell, but not in sync with the fed funds rate, which was cut sharply. The lag occurred because markets took time to believe that inflation was truly under control. Long-term yields remained “anchored” to past inflation expectations and only slowly decreased as confidence in disinflation grew.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

After this tumultuous period, the U.S. economy experienced lower inflation in the 1990s, which strengthened the link between the Fed funds rate and long-term yields; however, it was still not a one-to-one relationship. For example, after the Fed cut rates in response to the 2001 recession, mortgage rates and Treasury yields declined, but not by the full amount of the rate cuts.

Next, during the Global Financial Crisis (2007-2009), the Fed slashed the federal funds rate to near zero percent. Still, mortgage rates remained elevated relative to Treasuries due to market dysfunction and heightened risk aversion.

Between 2009 and 2011, the federal funds rate was near zero. Still, the 10-year Treasury yield and 30-year mortgage rates never fell below 3.0% due to the following factors: lingering risk aversion, many nonbank mortgage originators were financially weak and unable to pass on lower rates to borrowers, and inflation expectations remained high.

Some Good News Between 2011-2014

As mortgage markets normalized and financial conditions stabilized, the spread between mortgage rates and the 10-year Treasury yield narrowed, allowing mortgage rates to fall. At the same time, inflation expectations began to moderate, and markets became convinced that inflation pressures would continue to moderate.

The Federal Reserve’s commitment to quantitative easing (QE), which involved large-scale asset purchases, also helped keep long-term yields low. Unlike today, U.S. Treasury markets served as a safety-haven for both domestic and foreign investors. In short, all factors aligned in favor of lower long-term interest rates. In early 2025, financial markets were surprised to see that as global policy uncertainty increased and U.S. stock markets declined, long-term Treasury yields did not fall.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

Reducing the federal funds rate by 200–300 basis points will not always lead to a proportional decrease in mortgage rates or the 10-year Treasury yield.

History demonstrates that long-term yields are influenced by expectations of inflation over the long term, concerns about recession, and broader financial market conditions that go beyond just fluctuations in the Federal funds rate. Historically, risk aversion and market dysfunction have often kept the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield and mortgage rates elevated, even when the Fed cuts rates. However, the drop in mortgage rates after 2011 underscores how anchored inflation expectations can play a crucial role in lowering long-term rates.

This may explain why the Federal Reserve is focused on convincing financial markets that it remains dedicated to reducing the inflation rate to its 2.0% target.

We leave it to the reader to decide whether lowering the Fed’s funds rate into an environment where we expect no recessions over the next 10 years and real GDP to accelerate from -0.5% in Q1 2025 to average growth rates of 2.4% or 3.0% can still lower longer-term inflation expectations and generate lower long-term interest rates.

On the other side of this argument, if markets become convinced that the one-time upward shift in inflation from the announced 20 to 50% tariffs and other factors signal the Federal Reserve won’t be able to meet its 2.0% inflation growth target, it will be challenging for long-term interest rates to mimic any declines in the federal funds rate.