The High-Stakes Gamble of Naming the Next Fed Chair Early: Should We Do it?

Former JPMorgan Chase Global Chief Economist (Ph.D. Economist) & Current Global Keynote Speaker

Source: Getty Images (Jessica McGowan)

Today, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the core PCE inflation rate, which excludes food and energy components and is the preferred inflation measure of financial markets and the Federal Reserve, rose at a yearly growth rate of 2.7%, surpassing the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target.

Against this backdrop, as the term of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell approaches its scheduled end in May 2026, a debate about the future Fed Chair has begun to simmer, not just about who should succeed him, but also when the next Chair should be nominated. Traditionally, sitting presidents wait until three to four months before their term ends to announce their nominee, allowing markets and the public to process the decision without unnecessarily politicizing monetary policy. However, some argue that President Trump, known for his frequent and blunt criticisms of Chair Powell, should nominate a successor much earlier, possibly even before the end of 2025.

In our nonpartisan review of this question, we evaluate the strongest arguments in favor and against the early nomination of the next Fed Chair.

The Case for Early Nomination

A sitting president, as the democratically elected leader of the country, is entirely within his rights to express views on economic policy, including monetary policy. While the Federal Reserve is independent, it is not unaccountable. The president oversees economic stewardship broadly and is ultimately judged by voters on the health of the economy. Therefore, expressing views — even if critical — may be part of a legitimate attempt to shape economic expectations.

President Trump has already been clear about his disapproval of Chair Powell’s leadership, famously calling him “a stupid person, a person of low IQ, and a dangerous person.” While such language is undeniably controversial, it leaves little doubt about Trump’s preferences. A formal early nomination of a like-minded Fed Chair could arguably enhance transparency. However, if markets already understand the president’s stance, codifying it through an early nomination would not be a surprise, but rather an affirmation.

Nominating a future Fed Chair early can also prompt broader economic debate. The Fed has established institutionalized forums, such as “Fed Listens,” to gain a deeper understanding of the views of households, businesses, and community leaders. Shouldn’t the views of a sitting president — and by extension, the electorate who voted for him — be afforded similar consideration?

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve regularly consults business leaders across its 12 districts to gather firsthand insights into economic conditions. It would be inconsistent to argue that corporate input is valuable while suggesting that elected political leaders should remain silent. Early nominations can stimulate necessary discussions, especially during times of economic uncertainty when clear leadership is crucial.

Just as forward guidance on interest rates stabilizes market expectations, knowing who will lead the Fed can anchor future policy expectations. During times of financial volatility or policy divergence, an early nomination could provide markets with a clearer view of future policy directions, especially if the next Chair has a well-established track record. Even if the Senate still needs to confirm the nominee, markets will adjust to the nomination as they do with other kinds of policy signals.

The Case Against Early Nomination

Numerous academic and institutional studies, including a respected 2024 analysis by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), provide evidence that central banks with less independence tend to experience worse macroeconomic outcomes. Specifically, these economies tend to suffer from higher inflation, lower growth, and more volatile exchange rates.

The United States is not immune. In 2025, the trade-weighted U.S. dollar index (DXY) weakened significantly, despite the Fed’s efforts to maintain credibility. While several factors influence the dollar, increased political pressure on the Fed has not helped. This erosion of central bank independence may deter foreign investors, making U.S. debt financing more expensive and ultimately contributing to inflation.

While presidents are free to voice economic opinions, announcing a successor to the sitting Fed Chair before their term ends can be perceived as a coercive act — an attempt to bend current policy by signaling that dissenters will be removed. Even if Powell is likely to finish his term, the looming shadow of a hand-picked replacement might chill open debate inside the Fed’s policymaking committee (FOMC).

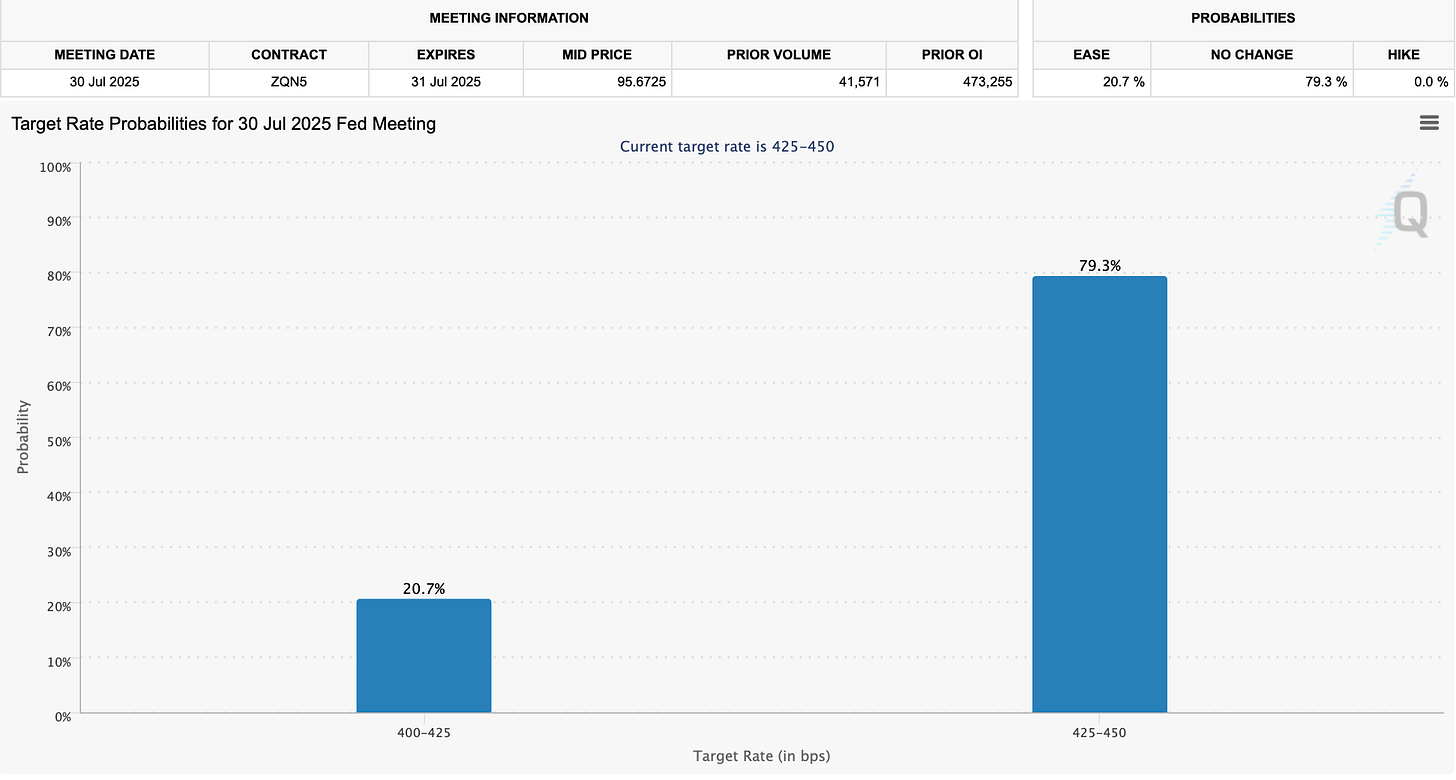

Some people will say that Fed Governors Waller and Bowman's recent comments about possibly cutting rates as early as July 2025, before the Fed reaches its 2.0% inflation target, when the futures market only gives it a 20.7% chance, are more about trying to make position themselves for the next Fed Chair nomination.

Source: CMEGROUP

The central bank’s strength lies in its perceived impartiality. Undue influence from the executive branch undermines this credibility. Suppose markets believe that rate decisions are being made to please the president rather than fulfill the Fed’s dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment. In that case, inflation expectations may become unanchored, with real economic costs.

The annual core PCE inflation rate, regarded as one of the best indicators for underlying consumer price inflation, increased by 2.7% in May 2025, according to a Bureau of Economic Analysis report released on June 27, 2025. That figure remains above the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

Another important counterargument to early political pressure is that Federal Reserve actions do not always lead to the expected market reactions. As I mentioned in one of my recent Substack articles, the Fed started cutting interest rates in September 2024 by a whole percentage point. However, instead of easing conditions, mortgage rates and the 10-year Treasury yield increased by approximately 60 basis points.

This divergence reflects multiple forces beyond the Fed’s control: inflation expectations, fiscal deficits, foreign central bank activity, and risk premiums. If markets interpret early political pressure as undermining the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility, long-term yields could climb even as the Fed lowers short-term rates. In such an environment, the president’s strategy could backfire, harming housing, investment, and economic confidence.

Have U.S. Presidents Ever Attempted to Influence the Fed?

U.S. Presidents from both parties have pressured Federal Reserve chairs. President Lyndon Johnson (Democrat) reportedly physically assaulted Fed Chair William McChesney Martin over disagreements about interest rate hikes. President Nixon (Republican) also bullied Chairman Arthur Burns, which many believe contributed to the runaway inflation of the 1970s. More recently, President Obama (Democrat) reappointed Ben Bernanke despite criticism and political backlash — a decision widely viewed as prioritizing central bank independence.

We leave it to the reader to decide whether such precedence justifies central bank independence or greater central bank control.

Summary and Concluding Thoughts

Nominating a Federal Reserve Chair far in advance of the incumbent’s term expiration is not in itself illegal or unconstitutional. But it raises difficult questions about how far presidential influence should extend over what was designed to be a technocratic institution.

Advocates argue that a president should not be muzzled when it comes to expressing economic views. They believe early nomination adds clarity and enables forward guidance that markets can digest. They also contend that voters elect presidents, not Fed Chairs, to shape the economy, and presidents should thus have a larger role in influencing monetary policy.

Critics counter that the damage to institutional credibility far outweighs any marginal benefit. They cite academic studies that politically influenced central banks yield worse economic outcomes and note that even the best-intentioned interference can erode investor confidence, weaken the currency, and fuel inflation.

Thus, the notion of influence is not new. The real question is whether codifying that influence through early nomination risks tipping the balance too far.

Advocates further argue that a president should not be muzzled when it comes to expressing economic views. They believe early nomination adds clarity and enables forward guidance that markets can digest. They also contend that voters elect presidents, not Fed Chairs, to shape the economy, and presidents should thus have a larger role in influencing monetary policy.

Critics counter that the damage to institutional credibility far outweighs any marginal benefit. They cite empirical evidence that politically influenced central banks yield worse economic outcomes and note that even the best-intentioned interference can erode investor confidence, weaken the currency, and fuel inflation.

As Chair Powell’s Fed term ends in May 2026, the U.S. President will need to decide not only who to nominate but also when. That choice will influence monetary policy and signal the broader direction of governance: whether it favors central bank independence and balance or leans toward consolidation and control.